The Poet's Block: Finding Inspiration Beyond the Familiar Landscape

The scent of linseed oil, the gentle rasp of a baren against paper, the quiet hum of focused concentration – these are the hallmarks of a Mokuhanga studio. But what happens when that studio feels… silent? When the inspiration, so vital to the creation of these beautiful prints, deserts you? It's a frustration familiar to any artist, but perhaps amplified in a tradition as steeped in history and aesthetic principles as Mokuhanga. For centuries, Japanese woodblock printing has captured breathtaking landscapes, serene portraits, and scenes of everyday life. Yet, to truly honor this tradition, one must find a way to move beyond imitation, beyond the comfortable territory of what’s been done before. This is the poet’s block, and breaking through it isn't about brute force, but a gentle exploration of the unexpected.

My own journey with Mokuhanga began with the predictable. Cherry blossoms, Mount Fuji – images ingrained in the collective consciousness of Japanese art. They were beautiful, certainly, and a necessary foundation for learning the techniques. The keying, the carving, the registration – all fundamental skills mastered through repetition. But a creeping sense of… sameness began to settle in. I found myself staring at blank blocks, the initial excitement replaced by a daunting emptiness. It was my grandfather, a man of few words but profound observation, who offered a surprising suggestion. He was a collector of antique accordions, a passion as unexpected as it was endearing. “Look at these instruments,” he said, gently running his fingers over the aged keys of a Hohner Marine Band. “Each one has a story. Not just of its maker, but of the hands that played it, the music it created. Find your story in the unexpected, and the block will break.”

His words struck a chord. I had been so focused on replicating the established beauty of Mokuhanga that I had forgotten the core principle: capturing *feeling*. The accordion, with its melancholic sighs and vibrant bursts of melody, possessed a depth of emotion that resonated far beyond its musical function. It was a story waiting to be told, not through imitation, but through the lens of Mokuhanga.

Beyond the Landscape: Finding New Subjects

The traditional subjects of Mokuhanga – landscapes, portraits, scenes from Kabuki theatre – are undeniably powerful. But limiting yourself to these confines can stifle creativity. To truly overcome the poet’s block, consider branching out. It's not about abandoning tradition entirely, but about infusing it with fresh perspectives. The very nature of wood itself offers narratives; understanding how wood grain narratives can truly inform your artistic vision is key.

Still Life with Unexpected Objects: Think beyond the predictable bowl of fruit. Introduce objects with character and history. My grandfather’s accordions became a series of prints. Not as literal representations, but as explorations of texture, light, and the passage of time. The intricate carvings on the accordion’s bellows, the tarnished metal of its keys, the subtle shifts in color caused by years of use – these details offered a wealth of visual information rarely found in a typical landscape.

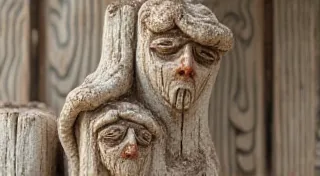

Urban Decay & Forgotten Spaces: The beauty of imperfection is often overlooked. Abandoned buildings, weathered signage, rusted machinery – these elements tell stories of resilience and change. Capturing the interplay of light and shadow on these forgotten spaces can be surprisingly evocative. The inherent texture of wood grain can mimic the distressed surfaces of crumbling walls.

Abstract Expression through Texture: Don't be afraid to abandon recognizable forms altogether. Focus instead on exploring the possibilities of wood grain and carving techniques. Create abstract compositions that evoke emotions and sensations rather than depicting specific objects. Think about the way a master carver uses the wood itself to create a visual rhythm, a dance of light and shadow.

The Power of Historical Context & Restoration

Understanding the history of Mokuhanga can be a powerful tool for breaking through creative blocks. Studying the works of masters like Hiroshige and Hokusai isn’t just about appreciating their artistry; it's about understanding the cultural and historical context that shaped their work. What were they trying to communicate? What were the prevailing aesthetic values of the time? Analyzing their techniques, their compositional choices, and their use of color can spark new ideas and approaches. The subtleties of achieving translucence in woodblock are also essential considerations – exploring the anatomy of light and understanding how it interacts with carved surfaces can open up entirely new creative avenues.

Furthermore, delving into the world of antique Mokuhanga prints – often fragile and damaged – provides unique insights into the printmaking process and the challenges faced by past artists. Restoration, even at a basic level, offers a fascinating window into the intricate details of the craft. Examining the layers of ink, the subtle variations in color, and the signs of age can inspire a deeper appreciation for the art form and spark new creative avenues. Of course, professional restoration requires specialized knowledge and skills; however, even a careful cleaning and stabilization can reveal hidden beauty and provide a fresh perspective.

The Accordion’s Lesson: Embracing Imperfection

My grandfather’s accordion wasn’t perfect. Its bellows leaked air, its keys stuck occasionally, and its finish was marred by years of wear and tear. Yet, it was these imperfections that gave it character, that told its story. Similarly, Mokuhanga doesn’t demand flawless execution. The slight blurring caused by the baren, the subtle variations in ink color, the occasional imperfection in the wood grain – these aren’t flaws; they are integral parts of the artistic process. They are the fingerprints of the artist, the echoes of the craft. Sometimes, it's the absence of detail that speaks volumes; considering how carving silence and a refined sense of negative space can dramatically enhance your compositions.

The very nature of inspiration is often fleeting and ephemeral; to capture that elusive quality requires a certain sensitivity and an understanding of how transient beauty shapes artistic expression. It’s about recognizing that ephemeral echoes of moments and experiences can be translated into powerful and evocative prints.

Beyond the technical aspects, consider the emotional resonance of your work. What story are you trying to tell? What feeling are you trying to evoke? Sometimes, the most beautiful prints are born not from meticulous planning, but from a willingness to let go and allow the art to unfold. The quiet power of imperfection can be a profound source of artistic inspiration, mirroring the natural beauty and inherent character found in the world around us. It’s about finding a balance between technical mastery and emotional honesty, creating works that resonate with both the eye and the heart.

My grandfather’s passion for antique instruments wasn’t just a hobby; it was a lesson in appreciating the beauty of age and the stories embedded within objects. Just as he cherished the history and character of his accordions, I now strive to honor the tradition of Mokuhanga while forging my own unique path. It's a constant process of learning, experimentation, and embracing the unexpected. The journey of an artist is rarely linear; it's a winding road filled with challenges, setbacks, and moments of profound inspiration. And it’s in those moments of connection – with the materials, with the techniques, and with the history of the art form – that we truly find our voice.