Ephemeral Echoes: How Transient Beauty Shapes Mokuhanga Expression

There's a certain melancholic beauty to old things, isn't there? Something about the cracks in the varnish of an antique accordion, the faded floral pattern on a grandmother’s quilt, or the subtle patina of aged copper that speaks to a history lived, a story weathered. I find myself drawn to these objects, not just for their aesthetic appeal, but for the silent testimony they offer to the relentless march of time. This same appreciation for transience, for the acceptance of imperfection born of decay, sits at the very heart of Mokuhanga, Japanese woodblock printing.

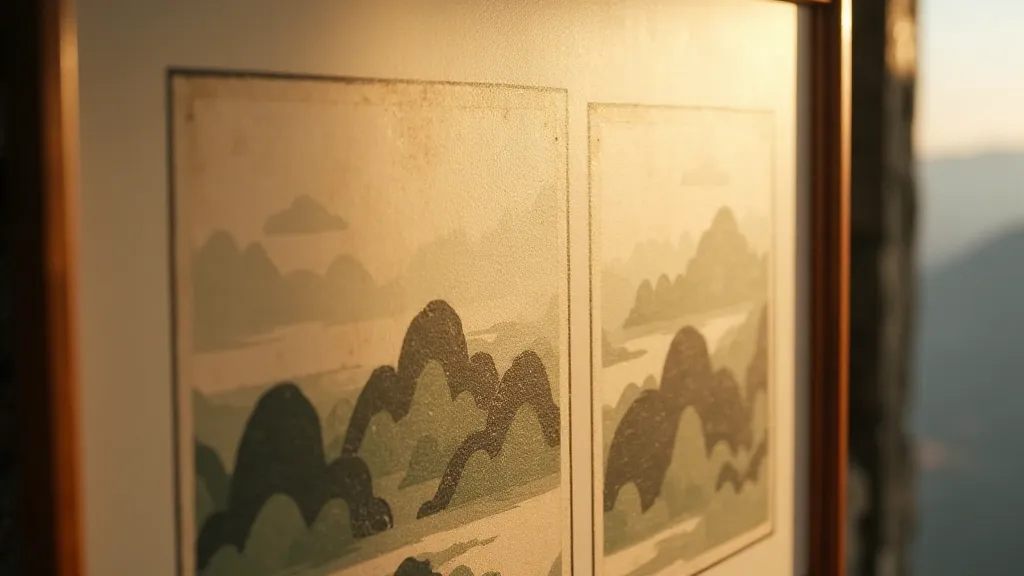

Mokuhanga isn't just a technique; it’s a philosophy, a visual embodiment of wabi-sabi, the Japanese aesthetic that finds beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and simplicity. It’s a world apart from the sharp, often aggressively defined lines of Western woodcut printing. The process itself contributes to this ephemeral quality. Unlike some other woodblock methods, Mokuhanga uses a softer wood, often cherry, which lends itself to delicate carving and the creation of subtle gradations. The carving isn't about brute force; it's about coaxing an image from the wood, a gentle persuasion that leaves its own mark on the block.

A History Rooted in Nature & Acceptance

The history of Mokuhanga is interwoven with the wider story of Japanese art. It evolved from earlier printing techniques, including Buddhist sutra woodblock printing, but truly came into its own during the Edo period (1603-1868). Ukiyo-e, the popular “pictures of the floating world,” are perhaps the most well-known examples, and while Mokuhanga played a role, many ukiyo-e artists used other printing methods. The modern revival of Mokuhanga in the 20th century, largely spearheaded by Sumi Kawashima, saw a renewed focus on the traditional techniques and materials, emphasizing the artistry and craftsmanship often overshadowed by the mass production of earlier printmaking. Understanding the visual language of these prints involves appreciating the subtle interplay between form and texture, a journey that can be further illuminated by exploring the broader theme of Wood Grain Narratives: The Imprints of Nature’s History.

Imagine the scene: a craftsman, painstakingly carving a block, knowing that each pass of the knife leaves a trace, a slight alteration in the wood's surface. There’s no erasing mistakes in woodblock printing; imperfections become part of the artwork’s narrative. A knot in the wood might dictate an unexpected line in the final print. A slight chip might be incorporated into the design. These aren't flaws to be hidden; they're opportunities to embrace the inherent unpredictability of the medium. The resulting compositions often transcend mere representation, venturing into an exploration of abstract forms and their inherent resonance – a concept beautifully captured in Beyond Representation: Abstraction and the Essence of Form.

The Watercolor Embrace: A Dance of Subtlety

The application of color in Mokuhanga is equally vital to its unique aesthetic. Unlike Western woodcut, which often uses oil-based inks, Mokuhanga uses vibrant, transparent watercolors. This process demands a delicate touch and a profound understanding of how the colors will interact. Layers are built up gradually, with each application subtly altering the previous one. This layering technique, bokashi, creates a soft, luminous quality that’s characteristic of Mokuhanga prints.

The act of painting the block itself is a performance of acceptance. The surface isn’s perfectly smooth; the grain of the wood affects how the watercolor adheres. Each block, even if carved from the same piece of wood, will yield slightly different colors and textures. The artist surrenders to these subtle variations, understanding that the final print is a collaborative effort between themself, the wood, and the watercolor.

Wabi-Sabi and the Beauty of Imperfection

The concept of wabi-sabi permeates every aspect of Mokuhanga. It’s a worldview that finds beauty in the weathered, the imperfect, and the transient. Think of the cracks in an antique ceramic bowl, the way the glaze has aged and shifted over time. Those aren't defects; they’re signs of a life lived, a story etched onto the surface of the object.

In Mokuhanga, the artist doesn’t strive for flawless reproduction. Instead, they embrace the subtle shifts and nuances that arise from the carving and printing process. A slightly blurred line, a subtle color variation – these aren’t mistakes; they're expressions of the inherent imperfection of the medium. They’re reminders that nothing lasts forever, that everything is subject to change. The fragility of the finished piece speaks to a deeper truth: that even the most seemingly robust objects eventually succumb to the relentless forces of time and entropy. The inherent vulnerability present within the wood itself resonates deeply, prompting reflection on the forces that shape and reshape the world around us – a concept beautifully explored in The Weight of Grain: Finding Strength and Vulnerability.

There's a profound sense of humility in this approach. The artist acknowledges that they are not in complete control of the outcome. They are working with natural materials, subject to their own unique properties and limitations. This surrender to the process fosters a sense of grace and acceptance.

Collecting & Preservation: Honoring the Transient

For those drawn to the beauty of Mokuhanga, collecting can be a rewarding experience. Original prints from the Edo period are rare and valuable, but contemporary Mokuhanga prints are increasingly accessible. When acquiring a print, it’s helpful to understand the process and the materials involved. Look for prints that exhibit the characteristic softness and luminosity of Mokuhanga. The paper used is also important; traditional washi paper contributes to the print's overall aesthetic.

Preservation is key to ensuring that these works of art endure. Store prints in a cool, dry place, away from direct sunlight. Framing under glass can provide additional protection. Handling prints with care and avoiding excessive exposure to light will help to maintain their delicate beauty for generations to come. The deliberate repetition of techniques and patterns used in Mokuhanga printing demonstrates a commitment to both tradition and innovation, creating a rhythmic language unique to this art form – an idea captured in Resonance and Repetition: The Rhythmic Language of Mokuhanga.

Thinking about antique instruments, the allure isn’t just visual; it's the feeling of connection to a previous owner, to a time and place long past. A Mokuhanga print holds a similar resonance, a quiet echo of the artist's hand and the beauty of a fleeting moment, beautifully captured and offered to us as a testament to the elegance of transience.

Beyond the technical aspects of Mokuhanga, lies a philosophical underpinning deeply rooted in the acceptance of change and the embrace of imperfection. The process embodies a mindful approach, demanding not only skill but also a willingness to relinquish control and allow the materials to guide the artistic journey. Each print is a testament to this delicate balance – a record of the artist’s intention and the inherent unpredictability of the medium.

The appeal of Mokuhanga extends beyond its visual beauty; it offers a pathway to deeper appreciation for the transience of existence. It reminds us that nothing remains unchanged, and that even in decay, there is a unique and profound beauty to be found. The prints serve as a visual meditation on the passage of time, inviting us to contemplate the impermanence of all things.

Further exploration of Mokuhanga reveals a commitment to sustainable practices, utilizing natural materials and traditional techniques that minimize environmental impact. This ethos aligns with the aesthetic principles of wabi-sabi.