Wood Grain Narratives: The Imprints of Nature’s History

There’s a certain melancholy that clings to antique accordions. Not a sadness of loss, necessarily, but a quiet reverence for the stories held within their bellows and keys. Each scratch, each faded decal, speaks of countless melodies played, hands pressed against the keys, laughter shared, and tears shed. It’s a similar feeling, I’ve found, that washes over me when I work with Mokuhanga, the Japanese woodblock printing technique. It’s a feeling that transcends mere artistic creation; it's a conversation with history, with nature, and with the unseen hands that shaped the tools I hold.

Mokuhanga, unlike Western woodcut, doesn't seek to eradicate the wood's character. Instead, it embraces it, celebrating the knots, the grain patterns, the subtle imperfections that are inherent to the material. It’s a philosophy that resonates deeply with my own appreciation for the beauty of age and the passage of time. I remember finding an old, neglected accordion at a flea market years ago. The leather was cracked, the reeds were unresponsive, and the once vibrant finish was dulled with grime. It felt almost sacrilegious to touch it, to disturb its quiet slumber. But I was captivated. The weight of its history felt palpable, a tangible link to a past I could only imagine.

A Brief History: More Than Just Prints

Mokuhanga’s history is interwoven with the broader narrative of Japanese art. While its roots extend back to Buddhist sutra printing, the technique truly blossomed during the Edo period (1603-1868). It was a democratizing force, allowing for the mass production of affordable prints that depicted landscapes, portraits, and scenes from everyday life. Unlike Western printmaking, which often focused on sharp lines and stark contrasts, Mokuhanga utilizes softer woods like cherry (sakura) and basswood, and a unique layering technique using water-based inks. This results in a softer, more watercolor-like effect, capturing the nuances of light and shadow in a way that feels uniquely Japanese.

The accessibility of Mokuhanga meant that it wasn’t solely the domain of established artists. Craftsmen and artisans played a crucial role, hand-carving blocks and mastering the intricacies of the printing process. Their skills were passed down through generations, contributing to a rich tradition of craftsmanship that is still evident today. Just as the accordion maker poured their skill into the instrument's construction, ensuring its resilience and expressiveness, the Mokuhanga artisan devoted themselves to the delicate carving and printing processes.

The Wood’s Story: Imperfections as Inspiration

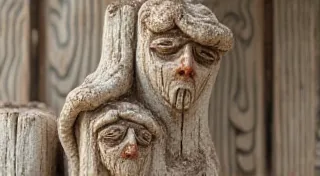

What truly sets Mokuhanga apart, and what I find most compelling, is its acceptance – even its celebration – of the wood's inherent character. We're trained, in many artistic disciplines, to strive for perfection. To smooth over imperfections. To eliminate anything that deviates from the intended design. But Mokuhanga teaches a different lesson. It demonstrates that the flaws, the knots, the subtle variations in grain – these are not problems to be solved; they are opportunities to be embraced. They are integral to the story the wood is telling.

Consider a knot in the wood. It’s a record of a branch that once grew, a testament to the tree’s struggle against the elements. It’s a reminder that even the most majestic trees face challenges. When I carve around a knot, I’m not erasing it; I’m acknowledging it, integrating it into the design. Sometimes, I’ll even use the knot itself as a focal point, allowing it to become an unexpected element of beauty. This is similar to how a worn key on an accordion tells a story of countless melodies played - a physical mark of the instrument's history and use.

Restoration and Appreciation: Listening to the Past

The same philosophy applies to the restoration of antique instruments. A purist might argue for a complete rebuild, meticulously replicating the original condition. But I believe that erasing the wear and tear is to deny the instrument its voice. The cracks, the scratches, the faded finish – these are all part of its story. They are a testament to its age and its use. Restoring an accordion, or carving a Mokuhanga block, isn’t about achieving a pristine replica of the original; it’s about preserving the integrity of its history, about allowing it to continue to tell its story.

Collecting antique accordions, like appreciating Mokuhanga prints, isn’t just about possessing a beautiful object. It’s about connecting with the past. It’s about acknowledging the hands that crafted it, the musicians who played it, and the audiences who listened. It’s about recognizing that every mark, every imperfection, holds a piece of that history.

Beyond the Design: A Dialogue with Nature

For me, the most profound aspect of Mokuhanga is the dialogue it fosters between the artist and nature. The wood is not simply a material to be manipulated; it’s a living entity, imbued with its own unique history and character. The artist’s role is not to impose their will upon the wood, but to listen to it, to respond to its inherent qualities, and to allow its story to emerge.

When I carve a Mokuhanga block, I’m not just creating a print; I’m engaging in a conversation with the tree that once stood tall and proud. I’m acknowledging its life, its struggles, and its legacy. And in doing so, I’m allowing its story to become a part of my own.

The echoes of that same sentiment resonate within an antique accordion’s bellows - a quiet reminder that beauty and stories can be found in the most unexpected places, even within the grain of a piece of wood, or the wear of aged keys.