The Breath of the Brush: Incorporating Calligraphic Sensibility

There’s a stillness in the workshop, a hush that isn't born of silence, but of intense focus. The scent of persimmon pigment hangs in the air, mingling with the faintest aroma of wood. I remember my first Mokuhanga workshop, feeling utterly overwhelmed. I’d expected technical challenges – the careful carving of the blocks, the meticulous layering of colors. What I hadn't anticipated was the emotional weight, the subtle dance between intention and surrender that permeates the process. It wasn's just about placing ink on paper; it was about breathing life into wood.

Mokuhanga, or Japanese woodblock printing, isn’s simply a craft; it’s a lineage. It’s a living testament to centuries of artistic devotion, intertwined with the broader tapestry of Japanese culture. While often associated with Ukiyo-e – the vibrant, popular prints of the Edo period depicting scenes of everyday life, actors, and landscapes – Mokuhanga's roots run even deeper, influencing and being influenced by calligraphy, a discipline considered the highest form of artistic expression.

The Dance of Line: Calligraphy as Inspiration

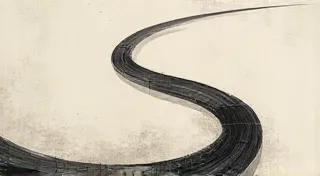

Consider the very essence of Shodo, Japanese calligraphy. It's not merely about replicating characters; it's about conveying the spirit and emotion of the written word. The thickness of a stroke, the angle of the brush, the subtle pressure applied – all contribute to a holistic expression. The blank spaces around the characters are just as important as the strokes themselves; they breathe life into the composition, creating a visual harmony. These deliberate pauses and negative spaces contribute immensely to the overall feeling, mirroring the quiet strength found in the best Mokuhanga prints.

This sensibility finds its echo in Mokuhanga. While Ukiyo-e prints often feature bold, graphic lines, the tradition of Mokuhanga emphasizes a more fluid, nuanced approach. The brush is our carving tool in a way, defining not just the form but the feeling of the image. Think of Hokusai’s “The Great Wave off Kanagawa.” It’s undeniably striking, but the power doesn’t solely reside in the sweeping curves of the wave itself. It’s in the subtle variations in the line quality, the way the brush hinted at movement and depth. That same care, that same attention to the breath of the brush, is what we strive for in Mokuhanga. This careful consideration and deliberate restraint is what differentiates a fleeting image from one that truly resonates.

In traditional Mokuhanga, the use of a single brush for carving is common. This fosters a direct connection between the hand and the block, imbuing the lines with a natural flow and organic feel. A sharp, rigid line feels manufactured; a line that pulses with life – that’s the mark of a practiced hand and a thoughtful approach. It’s through this meticulous process, this dedication to the details, that the wood itself begins to speak, revealing its own character and influencing the final design. And often, the resultant art evokes a sense of absence, a quiet contemplation that’s deeply rewarding – a feeling explored more deeply in Carving Silence: Finding Resonance in the Absence of Detail.

Beyond the Image: The Spirit of Wabi-Sabi

The beauty of imperfection – that’s the heart of Wabi-Sabi, another core Japanese aesthetic principle. It embraces the transient, the flawed, the simple. It’s a philosophy that resonates deeply within Mokuhanga. Unlike Western printmaking, where a perfect, repeatable print is often the goal, Mokuhanga embraces the subtle variations that arise from the hand-carved blocks and the water-based pigments.

Each print is unique. A slight shift in the carving, a minute inconsistency in the application of pigment – these aren't seen as errors; they's acknowledged as part of the character of the piece. This acceptance of imperfection allows for a more intimate connection between the artist and the work, and allows the viewer to appreciate the hand-made nature of the print. The embrace of these imperfections demonstrates a profound respect for the inherent qualities of the materials and the process itself, allowing the natural beauty to shine through. This philosophy isn't just applicable to visual art; it extends to all aspects of life, influencing everything from architecture to tea ceremony.

Collecting older Mokuhanga prints can be a deeply rewarding experience. Look for prints that show the evidence of the hand – the slight blurring of lines, the subtle variations in color. These aren’t flaws; they's hallmarks of authenticity, a tangible link to the artist and the time in which the print was made. Beware of prints claiming to be antique that show *too* perfect registration and consistent color, as these may be modern reproductions attempting to mimic the look of the old masters. These reproductions often lack the essential spirit of the original, failing to capture the quiet depth found in genuine, aged prints.

Embracing the Process: A Personal Journey

My own journey with Mokuhanga has been one of constant learning, of letting go of preconceived notions and embracing the unexpected. Early on, I tried to force precision, striving for perfect symmetry and uniform lines. The results were stiff and lifeless. It was my sensei, a quiet, unassuming man with hands stained ochre from decades of pigment mixing, who gently guided me towards a different path.

"Feel the wood," he would say, "Let the brush lead you." He wasn't talking about technical skill; he was talking about connecting with the spirit of the process. And gradually, I began to understand. He emphasized the importance of respecting the medium, recognizing that the wood itself possesses a voice. He taught me that true artistry lies not in controlling the process but in collaborating with it, allowing the materials and techniques to guide the creative outcome. He often spoke of the deliberate absence of detail and how that silence could speak volumes, a concept explored in more detail in Carving Silence: Finding Resonance in the Absence of Detail.

It's about recognizing that the wood itself has a voice. It resists, it yields, it shapes the lines we carve. It's about listening to that voice, and allowing it to inform our artistic choices. It's about allowing the imperfections – the slight wobbles, the unexpected shifts – to become part of the story. The color palettes used often have a profound influence, evoking specific atmospheres and moods— a study that's deeply explored in Chromatic Resonance: The Palette as Portal to Atmosphere in Mokuhanga.

Restoration and Appreciation: Respecting the Legacy

The care of older Mokuhanga prints requires a delicate touch. Avoid direct sunlight, which can fade the pigments. Store prints flat, protected from dust and humidity. Simple archival mounting techniques can provide stability without compromising the integrity of the artwork.

More than that, however, appreciating Mokuhanga involves understanding its historical context and the cultural values it embodies. It’s about recognizing the dedication and skill of the artisans who created these prints, and the lineage of artistic tradition they represent. Recognizing the way the prints echo a moment in time, documenting a culture through visual story telling—and sometimes, even leaving ghostly impressions behind – a fascinating topic discussed in Ephemeral Echoes: The Ghost Impressions of Mokuhanga.

It’s a deeply personal experience, one that connects us to a rich and enduring legacy. The breath of the brush – the intentionality, the fluidity, the acceptance of imperfection – these are the qualities that truly define Mokuhanga, and that allow us to glimpse into the heart of Japanese art.