Ephemeral Echoes: The Ghost Impressions of Mokuhanga

There's a particular melancholy that clings to antique accordions. Not a sadness of loss, precisely, but a poignant awareness of countless melodies played, countless hands coaxing life from bellows and keys, countless moments held within the instrument’s resonant chambers. The cracks in the wood, the fading gold leaf, the subtle dust of years – they tell a story of transient beauty, of something both cherished and slowly returning to the earth. This feeling, this resonance with the fleeting nature of things, is perhaps the closest Westerners can get to understanding the essence of Mokuhanga, Japanese woodblock printing.

We often fixate on the final, vibrant print – the rich blues of Hokusai’s waves, the delicate pinks of Yoshitora’s courtesans. But within the process of Mokuhanga, there lies a secret layer, a subtle poetry rarely discussed: the ghost impression.

Understanding the Layers of Mokuhanga

Before we delve into the intricacies of the ghost impression, let's briefly review the core principles of Mokuhanga. Unlike Western woodcut techniques that typically use a single block carved in relief, Mokuhanga traditionally employs multiple blocks, each corresponding to a specific color. The artist meticulously carves each block, applying a water-based pigment to the surface and pressing it onto washi (Japanese paper). This process is repeated with each block, gradually building up the image, layer by layer.

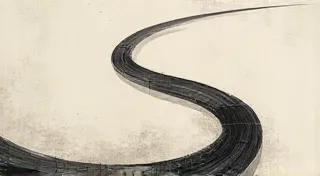

What many don’t realize, or give due consideration to, is the possibility – and often the deliberate intention – of creating a ‘ghost print’ or 'kaisho' – a lightly imprinted layer derived from a previously used block. It’s not a mistake; it’s a deliberate choice, an invitation to embrace imperfection, and a powerful tool for creating depth and nuance.

The Philosophy of Kaisho: Embracing the Fleeting

The concept of kaisho isn't simply about a technical process; it’s deeply rooted in Japanese philosophy, particularly Zen Buddhism and the appreciation for wabi-sabi - the acceptance of transience and imperfection. The Japanese aesthetic finds beauty not in the flawless, but in the weathered, the worn, the asymmetrical. A perfectly symmetrical teacup isn't as valued as one with a slight irregularity in its form. Similarly, a woodblock print that perfectly replicates the carved image isn’t as intriguing as one that holds the echo of previous impressions.

Imagine a musician returning to a worn string on their instrument. It might not resonate with the same clarity as a new string, but it possesses a unique timbre, a history, a subtle fragility. The kaisho is that worn string – a whisper of the previous layer, barely visible, yet profoundly affecting the overall feel of the print.

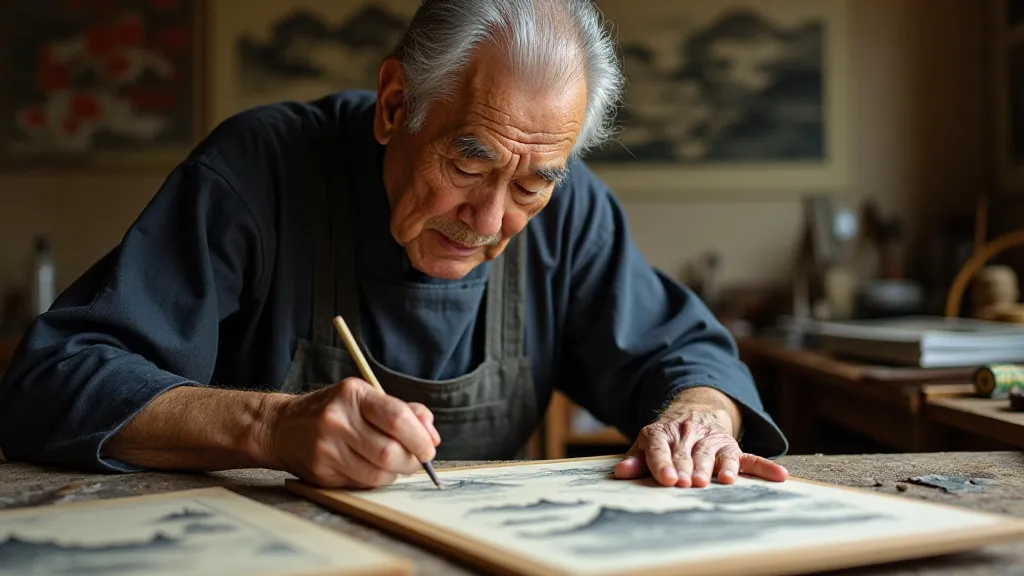

Historically, this was frequently done with the key block, the block representing the core imagery. The artist might print this block initially, then use it again, with a lighter application of ink and a reduction in pressure, to create a subtle, almost ethereal overlay on the subsequent layers. This technique could soften edges, add atmosphere, or even introduce a sense of visual depth.

Crafting the Subtle Echo: Technique and Intention

Creating a successful kaisho isn’t as simple as just printing a block again. It requires an intimate understanding of the inks, the wood, and the paper. The artist must carefully control the amount of ink applied, the pressure exerted during printing, and the moisture content of the paper. Too much pressure and the kaisho will overwhelm the other layers; too little and it will be indistinguishable from the paper itself.

The inks themselves play a crucial role. Traditional Mokuhanga inks are water-based, which means they are easily manipulated and readily absorb into the paper. This creates a soft, almost velvety texture that is unlike anything achievable with Western oil-based inks. The very nature of the ink lends itself to this layering process, creating a unique aesthetic.

Think of the finest calligraphy – the subtle variations in brushstroke that convey not just meaning, but emotion. The kaisho is the equivalent of that subtle nuance in printmaking, a whisper of intention that speaks volumes to the informed observer. It’s a mark of a master craftsman.

Collecting and Appreciating the Kaisho

For collectors of Mokuhanga, the presence of a deliberate kaisho is often a sign of exceptional quality. It demonstrates not only technical skill but also a deep understanding of the artistic principles behind the process. Prints with well-executed kaisho often command higher prices and are highly sought after by connoisseurs.

However, it's important to note that not all "ghost images" are intentional kaisho. Sometimes, they are simply the result of uneven ink distribution or inconsistencies in the woodblock. The discerning collector must be able to differentiate between the two. The intentional kaisho possesses a subtlety and a purpose that is absent in unintentional markings.

Restoring a damaged Mokuhanga print, especially one featuring intentional kaisho, requires a particular delicacy. Any attempt to remove or conceal these subtle impressions risks destroying the very essence of the work. The goal should be to stabilize the paper and repair any tears, while preserving the integrity of the original image, including its ephemeral echoes.

The Enduring Legacy of Transient Beauty

The ghost impression in Mokuhanga is more than just a technical trick. It's a powerful symbol of the transience of beauty, the importance of embracing imperfection, and the profound connection between art and philosophy. It’s a reminder that even as things fade and change, they leave behind echoes – subtle impressions that speak to the enduring power of the human spirit. Like the melodies coaxed from an antique accordion, these echoes resonate with a poignant beauty that transcends time.