Wood as Witness: Documenting Time Through Mokuhanga

There's a profound melancholy that clings to antique accordions. I own one, a Hohner Marine Band from the 1930s, its bellows cracked and its once-bright finish faded to a ghostly patina. It's not beautiful in a conventional sense; it’s beautiful because it holds stories. It whispers of smoky dance halls, of wartime longing carried across oceans, of countless hands pressing its keys, coaxing music from its reeds. And it’s this sense of time held within an object, of history etched into its very being, that resonates so deeply with the art of Mokuhanga, Japanese woodblock printing.

Mokuhanga isn’t just a technique; it's a tradition imbued with a quiet reverence for materials and a deep connection to the passage of time. It's more than creating a pretty picture; it’s about capturing a moment, a feeling, a cultural snapshot for posterity. While Ukiyo-e, the more familiar style of Japanese woodblock prints, focused on vibrant depictions of courtesans, landscapes, and actors, Mokuhanga, evolving alongside it, often adopted a subtly different approach - a stillness, an understated elegance that lends itself beautifully to documenting the era in which it was created.

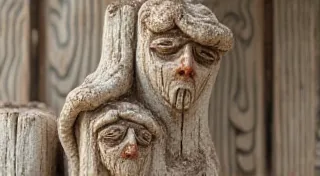

The Enduring Nature of Wood

The very essence of Mokuhanga—the use of wood—is crucial to its ability to act as a historical record. Unlike mediums like oil paint or watercolor, which are susceptible to degradation over time, wood possesses an inherent longevity. The cherry wood used traditionally for Mokuhanga blocks, properly cared for, can last for centuries. Consider that many Mokuhanga prints from the Edo period (1603-1868) survive remarkably well today, offering tangible links to a vanished world.

This resilience allows the prints themselves to become silent witnesses. Think of a print depicting a bustling marketplace in 18th-century Osaka. It's not just a representation of merchants and shoppers; it's a document. It records the fashion of the time, the architecture, the types of goods being traded, the expressions on people's faces. Decades, even centuries later, that image offers a window into a lost way of life, a direct connection to the people who inhabited that time.

Craftsmanship and Cultural Shifts

The process of Mokuhanga itself reflects a culture of meticulous craftsmanship and a dedication to preserving traditions. The creation of a single print involves a complex collaboration. The artist designs the image, but the design is then transferred to a woodblock carver, who painstakingly chisels the image into the wood. The printer, often a separate specialist, then uses the block to create the print. This division of labor fostered a hierarchy of skills, and the quality of each step directly impacted the final product.

As Japan underwent significant cultural shifts, those changes were subtly reflected in the Mokuhanga of the time. The Meiji Restoration (1868) ushered in a period of rapid modernization, as Japan opened up to the West. This is visible in some prints: the introduction of Western clothing, the appearance of steamships in harbor scenes, and the gradual decline of traditional Japanese attire. While Ukiyo-e, catering to a broader audience, often embraced these new influences with a certain theatrical flair, Mokuhanga often depicts them with a more contemplative stillness, as if observing these changes with quiet understanding. They are like old photographs, documenting not just what was there, but the mood and feeling surrounding it.

Preservation and Collecting: Listening to the Past

The preservation of Mokuhanga prints is, in many ways, an act of historical preservation. Antique prints, particularly those from the Edo period, are fragile and require careful handling. They are susceptible to fading, insect damage, and mold. Collectors and museums often employ specific archival techniques to protect these treasures, understanding that each print represents a precious link to the past.

Collecting Mokuhanga isn't simply about acquiring beautiful objects; it’s about engaging in a dialogue with history. It’s about appreciating the skill of the artisans who created these prints and the cultural context in which they were made. A collector’s knowledge extends beyond aesthetics—it includes a grasp of the historical periods, the prominent artists, and the techniques used to create these unique works of art.

Restoring antique Mokuhanga is a delicate process. Unlike some forms of restoration that involve aggressive cleaning or repainting, restoration of Mokuhanga typically focuses on stabilization—repairing tears, reinforcing weak areas, and preventing further deterioration. The goal is to preserve the print’s original integrity, allowing it to continue whispering its story for generations to come.

The Legacy Continues

While the peak era of traditional Mokuhanga production might have passed, the art form continues to thrive today. Contemporary artists are embracing the techniques of their predecessors, using woodblock printing to explore new themes and perspectives. They are recognizing, perhaps intuitively, the enduring power of wood to capture the essence of their own time. These contemporary prints, too, will become historical documents, offering future generations a glimpse into the anxieties, hopes, and aesthetic sensibilities of the 21st century.

The melancholic beauty of my antique accordion, the quiet wisdom etched into each woodblock print, the shared understanding of time and memory—they all point to the profound value of preserving our cultural heritage. Mokuhanga, as a medium, possesses a unique ability to do just that. It allows us to connect with the past, to appreciate the artistry of those who came before us, and to contemplate the fleeting nature of time. It is a testament to the enduring power of art to document, preserve, and transmit the stories that define us.